Horizon Forbidden West is one of my favorite games of recent years. I always find myself getting sucked into its addictive world design. So I decided to analyze it more and share my findings here as a love letter to the game. For this analysis, I will talk about two different methods (that I believe) Guerrilla uses to make the world of Horizon so damn fun to be in. Those two methods are World-Systems and World-Narrative.

What is World-Systems design?

World-Systems design is a relatively unknown niche in World Design. There are few sources on the subject matter online, mostly because these techniques are applied in AAA studios more so than in smaller studios. However, that does not stop me from wanting to master it. At its core, World-Systems is a way of combining the Gameplay Systems within the World Design. This creates a link between the game and world, increasing the immersion and improving the gameplay loop.

How is it implemented?

Saving & Fast Travel

We start off with a fairly straightforward system, players can save their game by lighting campfires. These campfires are placed all over the map. When a player saves their game at a newly discovered campfire, they will unlock a fast travel point. This way, players can manipulate the world, in the form of lighting a campfire, by saving their game.

It also cleverly combines with the fast travel system, which works well in open-world games.

Enemy Encounters

This is by far the most popular way of including game systems in the world.

It creates conflict, which sparks problem-solving and creativity in the player. But it also acts as a way to let them interact with various systems.

For example, the elemental system. This system creates weaknesses and strengths for machines, and inclines players to use a certain weapon/element to defeat them. This is mostly Combat Design. Which is something I won’t go into now, but it works in tandem with World-Systems.

Generally, bigger enemies use more combat systems. So a misplaced enemy can overwhelm or bore the player. This is why World designers need to understand every system in the game.

In this case, different enemies drop different resources and XP amounts. So this means that the placement of machines directly influences the player’s progression. Since access to machines is access to weapons and experience/skills.

This connection showcases that higher-level machines drop better crafting materials that help me kill more higher-level machines. Concluding in one giant positive feedback loop, which we call Progression.

The job of the World designer would be to recognize this system and balance it according to what level the player’s level, and what items the designers want to give to the players.

You can see that Designers steadily increase the enemy amount & variety based on where the player should be in the game. Of course, there are more factors at play, but Enemy encounters are a beautiful example of controlling what systems the player uses and when.

Machine Overrides

Machine overrides are a beautiful case of World-Systems, and here’s why:

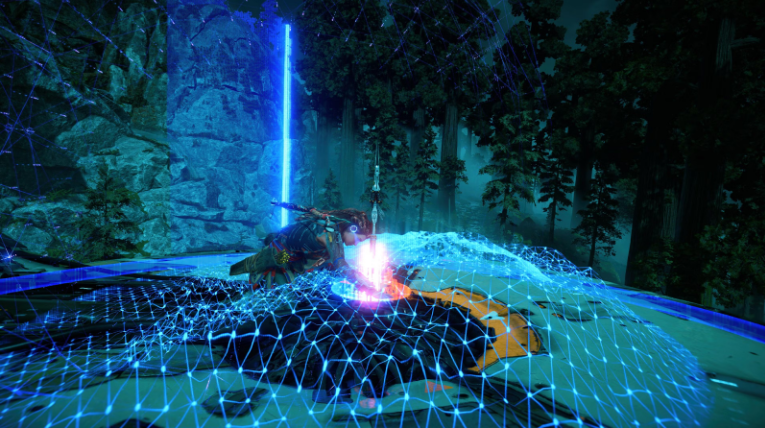

Overriding a mechanic in Horizon, where Aloy can hack machines and, in a sense, “tame” them. Depending on the machine, they can be used as companions in battle or as a way of transportation

This gives machines another purpose besides being farms for Loot and XP.

So already, Designers can give players different ways of transportation based on the enemy encounters.

But the most interesting part is how players obtain Overrides. You see, the player first has to unlock the ability to override certain machines. This is done via Cauldrons! Cauldrons, in Horizon, are the “factories” where the machines are made. Cauldrons narratively fit very well in the world of Horizon, mainly since the existence of these machines is what makes Horizon so interesting.

These Cauldrons are mostly linear dungeon-like experiences, light on puzzles but focused on traversal and combat.

When the player has completed a Cauldron, they get rewarded with several machine overrides. This means that players need to interact with the world to be able to override machines.

It would have been super easy to tie machine overrides to the level of the player, but the Cauldrons give more varied gameplay and context to the world. This all combined increases the immersion and fun in the game. Of course, the Cauldrons vary in recommended player level. This is likely to control what overrides the player has in every stage of the game. Connecting World-Systems to progression again!

Greenshine & Brimshine

Greenshine & Brimshine are both gems that can be found while exploring the world of Horizon. Greenshine can only be found in the main map, whereas Brimshine can only be found in the DLC map.

Greenshine can be found in different rarities; it ranges from fragments to slabs. Brimshine only comes in one rarity, but the amount per cluster differs based on difficulty to obtain. For example, a Brimshine cluster with a boss fight nearby increases the difficulty to obtain; therefore, you get more Brimshine. Both of them are found at locations across the map, encouraging exploration.

Greenshine is a resource that can be used to upgrade weapons in different rarities. Usually, the rarer the greenshine, the higher the level upgrade. This directly ties world exploration to the gear upgrade system/progression.

Brimshine is also used for upgrading gear, but also for buying new gear. This is most likely done to prevent high-level players who enter the DLC from instantly buying the new gear. Encouraging exploration.

Tall Grass

Tall grass is more catered towards Combat Design and its systems, but I felt like I needed to mention it here. Placement of grass can directly influence moment-to-moment play instead of progression, which makes it an interesting candidate.

For example, because there is grass, I am more encouraged to play stealthily or override machines. Because the World Designers placed grass here, I am more inclined to use the Stealthy Combat Systems.

Whereas the area here contains less grass, and is therefore more difficult to play stealthily. This makes my chances of facing the Enemy head-on more likely.

The tall grass might not be the most complex system, but it is an interesting moment-to-moment World-Systems case.

Tallnecks

Tallnecks are the most elegant machines in the Horizon franchise, and their use is unique, too. Since this is the only machine that the player cannot kill.

Instead, it interacts with the Override System and Map System. Players would need to find creative ways to climb the Tallneck, with the goal of eventually overriding it. Once the Tallneck is overridden, it will reveal a great portion of the map area around it.

For example, this Tallneck would reveal everything in the red circle. So Tallneck acts as a bridge between the Game and the Minimap.

Techniques for Implementing World-Systems

World-Systems is generally used to create an intuitive bridge between the game’s mechanics/systems and the game world. “Connecting Islands”, was said by Guerrilla Games’ Lead Designer Eric Boltjes in his GDC talk, Horizon Zero Dawn: A Game Design Postmortem. World-Systems makes the world feel alive, and therefore closely works with Narrative to create context for these World-Systems. A strong Narrative can allow World-Systems to work more focused and become more creative. Now let’s see how we can work on World-Systems.

The Game

Before one can start creating World-Systems, there needs to be a strong sense of what the game will look like. What will the Gameplay be? Is there going to be Combat? Are there going to be Enemies? What is the Gameplay Loop? What will the Game Economy be? These do not necessarily need to be set in stone, but the direction needs to be clear and permanent.

The Narrative

A narrative can really help add more context to potential World-Systems, or set you in a certain direction of thinking. World-Systems is all about connecting the game and increasing immersion, so it only makes sense to apply a concrete narrative to your design. A narrative should NOT prevent ideas from emerging, however. That is why the timing is super important; first, define the main gameplay elements before adding a narrative. The Narrative should act as a way for organic World-Systems to grow from established game elements.

The Goal

Arguably, the most important aspect of any feature is the goal. Why should we add this? Why is it designed in this particular way? What do I want to achieve? How does this fit within our game? What do I want my player to do?

For Example, the game is set in a Fantasy setting and contains Gold Currency. This means that there should be a way to get that currency. If I want my player to explore the map, I could place lost treasures across the world that contain gold. If I want to make exploring optional, then I would need multiple different ways to obtain Gold; Bounty hunts, helping villagers, or selling items can make the game more enjoyable for different types of players.

By creating variety in World-Systems, you can make the game more accessible and interesting. In Horizon, you have multiple ways of obtaining skill points and XP. This makes the game more rewarding for explorers and completionists, but also more accessible for less-skilled players. The goal here was likely to encourage the Open-World.

Creating a goal for your World-System greatly increases the value of the set World-System by being able to focus attention on encouraging playstyles, exploration, and/or curiosity.

The Reward

Rewards come in many different forms; they, too, should be given with a certain goal in mind. For example, I want to encourage my player to try the weapon upgrade system; therefore, this treasure chest could contain an item that can upgrade a weapon of choice. This way, players will look for chests to upgrade their weapons.

A reward shouldn’t be limited to the economy, however. In the Tall Grass example. Technically, it is a World-System, but you don’t get anything for using it. What you do get is easier access to different playstyles. For example, when in Tall Grass, it’s easier to stealth kill or override machines. The reward could be an opportunity in this case.

A reward is usually given at the end of a successful task/quest/objective/exploration. This means that the reward should be used as a hint for the next objective, an intrinsic motivator, or a reminder of their completed task.

The Spice

And lastly, we need to add a bit of “Spice”. Spice is the variety in this case. Because variety is the spice of life. A good example of this is in the Greenshine & Brimshine case. When exploring the map, brimshine can be found in different locations. Sometimes, on the sides of cliffs, others in ancient ruins, and sometimes it has machines guarding it. Fundamentally, it changes nothing about the World-System itself, but it changes how the gameplay leads up to it. Resulting in a very fun experience collecting it.

An example of a similar system without “The Spice” can be seen in the recent Pokémon Scarlet & Violet. Where there are small collectables hidden across the world, at first, it’s really fun collecting these little things while exploring the map. After a little while, it already starts to bore, this is likely because there is no varying factor except their location. Therefore, it makes it feel like a massive chore.

Adding variety, or opportunity for variety, to a World-System will greatly improve the fun and excitement of interacting with it.

World-Narrative use in Horizons world

Visa Points

Visa points are an on-the-nose example of visual storytelling. Because of the post-post-apocalyptic setting allows the narrative team to create an “before and after” image.

Designers use this to their advantage, by creating these small visual quests, the goal is to align the given image with its real-world counterpart. Creating the full image of the past. The argument could be made that this is part of World-Systems as well, since the player needs to use core gameplay mechanics to interact with it. However, it is still a great narrative tool.

Visa points are very on the nose and literally give you a glimpse of the past. Although this could be perceived as “too obvious”, it is nice to know what bigger structures were used for. Especially when they are inhabited in the present day.

It is nice to get context in significant world locations. It helps make the place feel more magnificent.

Black Boxes

Black boxes are remnants from the old world planes that tell sad stories about the pilots’ last moments. These are audio files that let you hear their last moments on the radio. Although the narrative is quite dark, it gives the player nice insight into what the last moments before extinction would have looked like.

These black boxes, in particular, are a great case of how “The Spice” can be used for story elements as well. There is quite a variety in how they approached their design. Some black boxes can be easily accessed, while others might come with a small puzzle. Sometimes tribes interpret them as a base they can use, connecting the past with the present. Or even combining black boxes with underwater mechanics, creating a sunken plane.

The black boxes are great in showcasing how designers can use Spice for storytelling to create interesting gameplay.

Relic Ruins

Relic Ruins are, what the name suggests, Old Ruins that contain Relics. This is an interesting combination of Narrative and Environmental Storytelling with Puzzle Design.

Relic Ruins are an old-world ruin that contains an ornament. Ornaments that can be used to light up the sky in Las Vegas (yes, I know, it sounds quite weird). These Relic Ruins count towards World-Systems as well, since again, it combine core gameplay mechanics and systems with in-world activities.

What is really interesting is that the designer chose to combine these puzzles with a narrative. Every Relic Ruin is a separate small story between people of the generation before. In the case of the example pictures, it was an office building with people just coming back from a party.

Most of the narrative is communicated between Data Points. The player usually needs to read to obtain a code, used to open a door.

Relic Ruins are a prime example of Designers combining different gameplay elements to create more opportunities for Narrative and vice versa.

Data Points

Data points come in many different forms and types; the consistent thing about all of them is that they add more narrative to their situation. Some of them are found during the main/side quests and give clues on how to progress. While others might be “randomly” found at sightings, adding a story to certain locations.

Almost all of them interact with the Focus mechanic. This makes the most sense since the Focus is Old World Technology as well.

Data points are an ideal way of adding context to a place/quest without having to implement cutscenes everywhere.

World Dressing

World dressing is the most popular way of converting a narrative into a level. You could even make the argument that Art is a way of communicating stories. This is not limited to games; it can be seen in paintings, movies, and even graffiti in cities.

In Horizon’s case, it’s everywhere. Even the armor Aloy is wearing fits the overarching Narrative of her hunting machines. But Art and Narrative can also be seen combined in the world, for example, this door that is being held open by a machine fossil.

It does not always have to implement gameplay; however, sometimes art can be there to tell microstories or to support the bigger story.

These art assets are equally important for immersion, as they both breathe stories and life into the world. Placement is most important here, however. Camping gear wouldn’t make as much sense on the bridge as it does in the cave. The images are examples of the difference between Micro and Macro Environmental Storytelling

The different methods of implementing Narrative in a Level & World

Before Implementing

There are different things you would have to consider before implementing Narrative:

- First of all, what is the narrative of this specific area? The story has to be clear before you can even implement it.

- Then, will this part of the level contain new gameplay? Gameplay has to go first, and narrative will support it. Before the narrative can be implemented, the gameplay has to be present. It is also good to keep in mind what kind of storytelling might complement the gameplay; not every cave would need a 10-minute-long cutscene to explain that someone camped there.

- What will the reward be? In some cases, a small story can be the reward, look at Black Boxes, for example. In that case, do you want to tell the story already through the environment? Or do you keep the mystery and let the reward be the reveal? Or how can a certain context twist player expectations?

- And finally, what kind of story am I telling? Will the story be on the Macro-Level? Micro-level maybe? Will it be part of the Main Quest or not? It is important to know this to keep in mind with budget & art constraints, not every story should be told on a huge scale.

Different Methods

Breadcrumbs

Leave small hints of what has happened in the level. This can be used to indicate the progress of the level, directions, or even hints.

A Glimpse into the Past

Instead of giving players hints, this gives players a complete image, but only for a certain area. Allowing them to feel the weight of the place.

Collectables

Collectables can be a fun way for completionists to interact with the story. In the Spider-Man games, for example, you can collect backpacks that are stuck to buildings, since Spider-Man always sticks his school backpacks to walls in the movies. This fits the narrative and adds a layer of gameplay to the game. You might even be able to connect these collectables to other systems.

Unveiling

Unveiling can be a way to suddenly reveal a level. For example, a player might be in an old facility, but once a door opens, it reveals what kind of facility. This can be an interesting way of subverting player expectations in a level.

Set Dressing

Dress the world according to the narrative. This is done via art and strategic placement, already discussed on World Dressing.

Storytelling through Gameplay

This is the most popular way of telling stories; the most common form of this is in Side Quests. It can also be done through small parts of gameplay, like opening, finding a key for a locked door, or opening that said door with a crowbar. Small differences in gameplay tell a completely different story.